The use of IPA

Imagine this: You are examining an interesting language that people around you are not familiar with. Now, because this is a language that's not too common, people don't know how to pronounce words in that language.

The questions is, how are you going to describe the sound in a written form?

You might say, "why not record it in the audio form or make a video?" The opportunity to hear the raw material is vital, as this is the primary resource for any sort of phonetical and phonological analysis, but you still need a system to describe the features to see the patterns. And, indeed, there is a writing system that (almost) accurately describes the sound.

The IPA is a description system used in linguistics - technically, it includes (or should include) all the articulation types in every language in the world. It was first published in 1888. There has been a lot of discoveries in languages all around the world ever since, adding new IPA symbols to the list, but also there are a lot of debates amongst the linguists about how to transcribe the sounds across different languages - or, more precisely, whether two different sounds in two distinct languages could actually be transcribed with the same IPA symbol, or if they should be transcribed differently.

You've probably encountered the IPA one way or another in a language textbook. You might not have "used" it, because nowadays most of them come with an audio material or you simply use an online dictionary to hear it spoken out loud. And, of course, when it comes to writing, you need to know the spelling in order to communicate in the language, not the IPA.

But it's actually potentially a useful thing; Although the main purpose of the IPA is to describe the sound, the great thing about it is, once you know which symbol represents what sound, you can make a prediction for how some unknown words are articulated, or even how to speak in a dialect (but you'll annoy the native speakers if you don't let them teach you alongside). Thus, some actors, especially when they have to speak in a foreign language or dialect in a play, they might get a sheet with some practice sentences written with the IPA.

When you try to improve your pronunciation using the IPA, you'll have to "learn" the new sounds, by which I mean you need to learn the articulation place, the position and the movement of the tongue or lips, and whether it's voiced or not. For that you might need an IPA table, so here's the link to a website:

Here you not only see the written descriptions of the features, but also hear how it's more or less supposed to sound like. Do feel free to play around with it, it's fun.

Sometimes it's hard to capture the phonological system in a language as a learner. There are a lot of reasons for this, mostly related to your mother tongue. Let's look closely at some major differences in some languages using the IPA symbols.

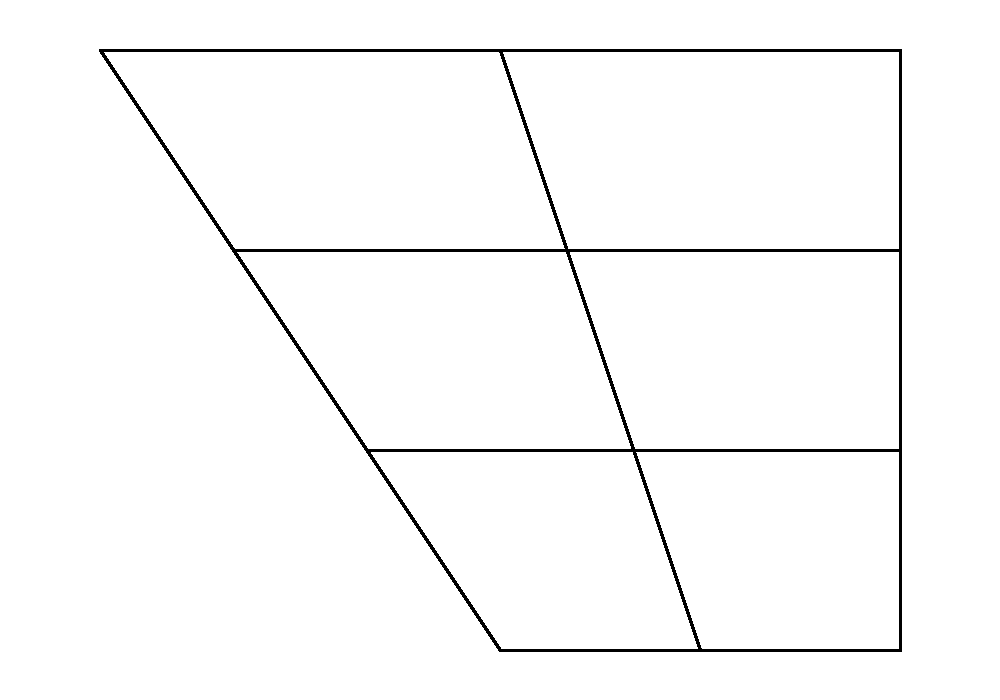

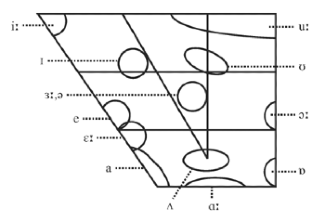

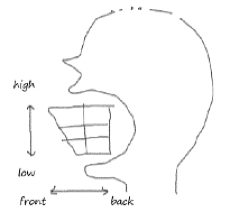

Take English as an example. The chart below shows the IPA of vowels in GB (General British)¹, more specifically the monophthongs of GB . In this kind of charts, the horizontal lines represent the backness of the articulation in the oral cavity (described with [+back], [-back]), while the vertical and diagonal lines represent the height (described with [+high], [-high], [+low], [-low]), where "high" means that the opening of the mouth is narrower, so you need to picture the position of articulation like shown in the drawing below². And when you see two IPA symbols right next to each other like on the diagram on ipachart.com, such as /ɪ/ and /ʏ/, or /ɑ/ and /ɒ/, the left one requires intense rounding of the lips.

And notice that the chart on ipachart.com contains /ɨ/ and /ʉ/, while the above shown variations of British English don't. This indicates that these don't exist in the latter, so it could take time for the English speakers to master the pronunciation of "ы (/ɨ/)" in Russian.³ So this is the part where you go as a learner, "I pronounce it wrong? But I'm doing the same as you!"

Usually, however, the most interesting, distinct phonological features of a language could be seen in consonants. /ʃ/ is a quite common sound across languages; Hungarian has it, English and German has it, and in my opinion Japanese as well in some certain contexts (just promoting my languages here). You create this sound by putting your tongue slightly behind the alveolar ridge - it's the sound of "sh" when you say "fish."

On the other hand, Russian is said not to have this sound - the closest it gets to /ʃ/ is with /ɕː/ (щ) and /ʂ/ (ш). I definitely struggled with these when I started mimicking Russian articulation. It took me a while till I realised that the tongue was creating sort of a vertical wall towards the hard palate with the /ʂ/ sound. My Russian teacher once explained that /ʃ/ is located somewhere between /ɕː/ and /ʂ/. But to be honest, I still haven't come to the point to clearly understand how to articulate /ɕː/, or how different it actually is from /ʃ/, so this is where I'm having the mother tongue-target language crisis. So long story short, with the knowledge of these differences, you can enjoy the accent the German speakers might have in Russian or vise versa, or recognise your own articulation pattern in a foreign language.

The analytic knowledge of the IPA description may come in handy if you're struggling with foreign accents like that. One of the strongest feature of the IPA is the symbols they use - if you already know at least one language in, say, Latin letters, it could be confusing how the same set of alphabets create a completely different sound in another language, for example '-tion' in some words in English (/-ʃən/) and German (/-t͡sɪɔːn/). But with IPA, each sound directly representing one specific articulation, it should feel less confusing (I hope).

Now, how we use IPA in linguistics, especially in describing phonological aspects of a language, could be a bit complicated. As you know from the experience, there are different pronunciation patterns in your own language, and, of course, across the languages around the world. Feel free to follow along with ipachart.com.

'R' is a good example here. When I compare the articulation in my languages, I seem to get a lot of variations. In English, depending on the dialect you speak, you likely and arguably get something like /ɻ/, /ɹ/, /ɚ/. The Hungarian 'r' often sounds like /r/ with the tip of the tongue tapping the palate more than once in a short period of time, while in Japanese /ɾ/ is more commonly observed, where the tapping occurs just once⁴. /ʀ/ exists in German, though nowadays less used than before (this one is hard for me to mimic) - in so-called standard German /ʁ/ is more commonly used.

Once you get used to the IPA transcription, you start to see - we could talk about which sounds could appear in different contexts, and put together the "sounds" that appear in different contexts with the same lexical function in a group (this is called allophones in linguistics; For example, think of the sound difference in "cats," "dogs," and "horses"; all of them with -(e)s at the end to indicate it's plural, but they are pronounced /s/ /z/ and /ɪz/ respectively).

Often I wonder if it shouldn’t be great if we knew how IPA works and textbooks for languages included IPA descriptions for sentences. Earlier, I gave you an example of actors practicing with IPA, and I think this is a great idea. First you’ll need to know which sound is represented by each of the symbols, but once you get the hang of it, it could be used as a strong guideline alongside with audios.

And here comes a bit of a more advanced part - if you're thinking of the same thing as me, then yes, apparently there are such things as IPA generators in this modern world! Keep in mind that they're not necessarily perfect, and they definitely do not reflect the dialectical variations, but let's see how an IPA translator transcribes a sentence I wrote, and you guess what it says. It's in an American accent, according to the AI (https://unalengua.com/ipa-translate?ttsLocale=en-US&voiceId=Salli&sl=en&text=)⁵:

həlˈo͡ʊ, ðˈɪs ˈɪz mˈiː sˈɪ.ɾɪŋ ˈɪn mˈa͡ɪ ɹˈuːm ˈɪts ɡˈɛ.ɾɪŋ wˈɔː͡ɹmɚ ðˈiːz dˈe͡ɪz, ˈænd ðˈə sˈʌn ˈɪz ʃˈa͡ɪ.nɪŋ a͡ʊtsˈa͡ɪd ˈa͡ɪ nˈiːd ˈæn ˈa͡ɪs kɹˈiːm

Get it? Can you catch what I'm saying here?

If you're as playful as I am, your next question would be, "Can I get the same sentence in an insanely thick German accent?"

... You probably didn't have the question at all, but I'm doing it anyways.

So here, all you need is to transcribe the whole text, but this time apply IPA symbols and transcription rules used for transcribing German.

And there you go, I made it for you! If you can speak like this, that should be German enough to ask for a citizenship:

ˈhaloː ˈdɪs ˈɪs ˈmiː ˈsɪ.tʰɪŋ ˈin ˈmaɪ ˈʁʊːm ˈɪts ˈɡə.tʰɪŋ ˈwɔː.mɐ ˈdiːs ˈdeɪs ˈʔend ˈdə ˈsʊn ˈɪs ˈʃaɪ.nɪŋ ˈʔaʊt.saɪt ˈʔaɪ ˈniːd ˈan ˈʔaɪs ˈkʁɪːm

... And that's it! That's one way or a tool for practicing a language, more precisely the pronunciation.

A very good old friend told me once that linguistics is just great for waffling. He may be right.

¹General British is the broader concept for standard British English. Compared to RP, Received Pronunciation, it contains regional variations as well, making it less conservative, unfocused on just one dialect.

²And please don't ask me how long it took me to draw this simple picture on my laptop.

³To be fair, I don't know if there's anyone at all who gets "ы" straight away on one go.

⁴This one is interesting. In Japanese there's neither 'r' nor 'l,' it's somewhere inbetween.

⁵In IPA transcription, /'/ shows the emphasised syllable and /./ where the syllable ends. The IPA generator doesn't show the syllable ending, so I added it to the AI-made variation.

*Figure 1: Cruttenden, Alan. (2014). Gimson's Pronunciation of English. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, eighth edition, New York, 330

*Figure 2: my own creation

Az International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) egy nyelvi leírási rendszer, amelynek célja, hogy minden nyelvben minden artikulációs típust tartalmazzon. Az első alkalommal 1888-ban kiadott IPA az idők során fejlődött új szimbólumok felfedezésével és a nyelvészek közötti folyamatos vitákkal. Amikor az IPA-t a kiejtés javítására használják, a tanulóknak meg kell ismerkedniük a hangok artikulációs helyével, nyelv- vagy ajakpozíciójával, mozgásával és hangzásával. Hasznos lenne, ha a nyelvi tankönyvek IPA-leírásokat tartalmaznának a mondatokhoz, lehetővé téve a tanulók számára, hogy jobban gyakorolhassák a kiejtést a hangforrások mellett.

Das Internationale Phonetische Alphabet (IPA) ist ein Sprachbeschreibungssystem, das darauf abzielt, alle Artikulationstypen in allen Sprachen einzubeziehen. Das 1888 erstmals veröffentlichte IPA hat sich im Laufe der Zeit mit der Entdeckung neuer Symbole und anhaltenden Debatten unter Linguisten weiterentwickelt. Bei der Verwendung von IPA zur Verbesserung der Aussprache muss man sich mit der Artikulationsstelle, der Zungen- oder Lippenposition, der Bewegung und dem Klang von Lauten vertraut machen. Es wäre vielleicht nützlich, IPA-Beschreibungen für Sätze biem Fremdsprachenlernen zu haben, damit die Aussprache anhand von Lautquellen besser geübt werden kann.

International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) は、すべての言語のすべての調音タイプを含めることを目的とした言語記述システムです。 1888 年に初めて発行された IPA は、新しい記号の発見や言語学者間の議論や批評により、時間の経過とともに進化してきました。 発音を改善するために IPA を使用する場合、口腔内での発音の位置、舌や唇の位置、動き、または有声・無声の特徴をおさえる必要があります。 外国語学習において、発音の練習として、音源とともにIPAで書かれた文章を併用することは効果的かもしれません。